Healthy plants need healthy soil for healthy growth. Plants need to be able to effectively absorb what they need from the soil for productive growth. Healthy soils allow for this to happen consistently. They do this through having diverse and abundant soil life, containing the full spectrum of plant nutrients, and being well-structured. The problem for agriculture, unfortunately, is that healthy soils have become very scarce.

We have found that one of the main factors contributing to the decline in soil health is the widespread use of chemical fertiliser. It has led to soils that no longer have thriving biology, and the life in the soil is the main driver of a healthy soil system. Before we get into how the biology does this, let’s first look into where it went wrong.

Blame the green revolution?

Renowned microbiologist, Dr. Elaine Ingham often says that the green revolution worked because we had already destroyed our soils and turned them into dirt. The widespread adoption and application of chemical fertiliser came at a time where there was no understanding of the long-term effects on the soil. For farmers, fertiliser was a miracle. Yields doubled and farmers were able to provide the required food for a growing population.

Now, after years of using chemical fertilisers, the effects on soil health have become apparent. Degraded soils mean fewer nutrients remain and plants are quick to become weak and diseased. This has resulted in further use of chemical fertiliser to top up soil nutrients as well as pesticides and herbicides to deal with the associated pest and weed problems. A conclusion one can draw from this is that we have set up our soils to be sick. Plants that are continuously given fertiliser will ultimately always become diseased. Fertiliser is the direct cause of the use of most pesticides. Maintaining this system is a costly business for farmers and is disastrous for the soil. In order to resolve the world-wide problem of over-fertilisation, the vicious cycle must be broken.

Getting out of the vicious cycle – enter the microorganisms

The question that we must ask ourselves is, how can we improve the health of our soils? The answer is surprisingly simple but requires some explanation. Just like every other organism on the planet, a plant does not function independently. Healthy growth of plants depends on a partnership between the plants’ roots and specialist bacteria and fungi. Plant roots, fungi and bacteria form a wonderful system, based on trading products. How does it work? Fungi and bacteria supply nutrients to the plant from the soil that would otherwise be hard to reach. In exchange for this, plants supply sugars that these microorganism use for food. To explain this system, I will explain bacteria and fungi separately.

Bacteria

Plants have a limitation; their roots have limited absorption ability. They only use 4 to 7% of the soil volume. The roots also don’t live long, only one to three weeks. To overcome this, plants use their absorption roots to forge a partnership. If they can’t find partners, they will die. If they succeed, it’s the start of a beautiful relationship. This relationship is formed between the plant’s root and soil bacteria. The bacteria that enter into this relationship with the roots are called rhizobacteria, aka root bacteria.

Rhizobacteria are specialists at mining nutrients from the soil. They mainly specialise in the mining of phosphates and nitrogen, which are very important for plant growth. These bacteria also carry out countless other important tasks. One of which is particularly special – they form a sort of a natural defense system around the roots. Anything attacking the plant is kept outside by the physical presence of these rhizobacteria. They make sure that there is no room for disease-causing bacteria. They also have their own interest in this, because the plant provides them with food so they can’t afford to give up that territory. These bacteria are not travelers though; their movement is only limited to around the root system. In other words, the bacterial colonies do not move back and forth from the minerals to the roots. This is where fungi come in.

Fungi

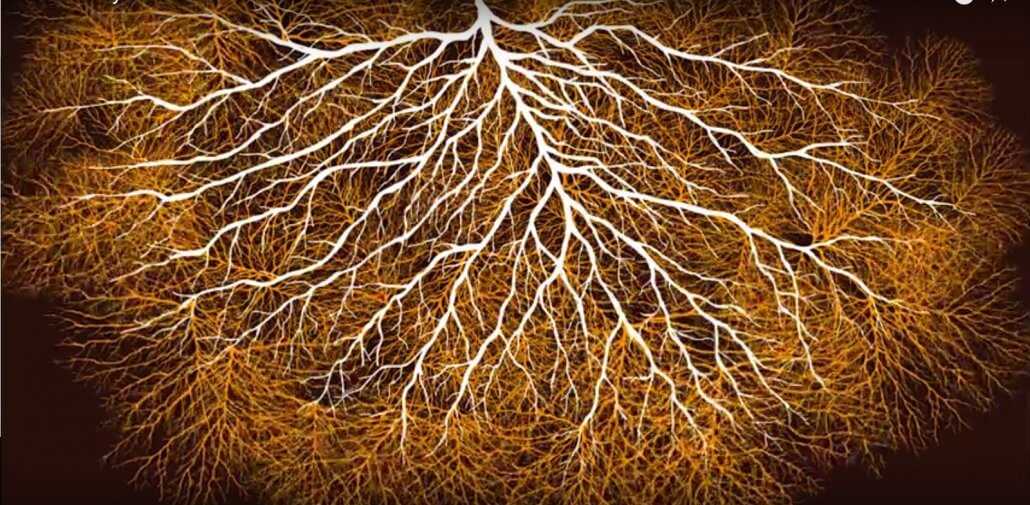

Most minerals found in the soil are located outside the reach of plant roots. As discussed above, this is also therefore out of the reach of rhizobacteria. The area of absorption by roots and bacteria is thus very limited. A specialised fungi group known as mychorhizal fungi are able to drastically increase this absorption capacity.

Mycorrhizal fungi: The plant’s secondary root system

Soil food web series: Does your soil have Wi Fi(ngus) connection?

Mychorrizal fungi form a living connection within roots. This creates an absorption and transport system between roots and the soil. The plants’ absorption roots are a lot thicker than that of fungi and can only go in-between macro-pores in the soil. By getting help from the mychorrizal fungi, whose threads are thinner, plants can gain access to the nutrients and water in-between the micro-pores in the soil. This is actually where most nutrients and water are stored.

When stretched out, these fine threads can easily be a kilometer long in just one teaspoon of soil. Mychorrizal fungi increase absorption capacity by 7 times on average; this means that growing can be done with less water. The benefit for the fungi is the food produced by the plant; for the plant, the benefit is a larger absorption zone. An added advantage of this relationship is the disease resistance which the fungal hyphae provide to roots.

Conclusion

The unique and constant interaction between plant roots, bacteria and fungi creates a fantastic symbiosis. Farmers are able to facilitate or limit this interaction through the practices they implement. The relationship can be enhanced by allowing plants to make use of the natural systems available, rather than us messing these up through bad management. Practices such as soil disturbance and over fertilisation destabilise this symbiotic relationship.

Healthy plants, with healthy roots, lead to healthier soils and therefore more productive plant growth.

Sources

- The management of soils with excessive sodium and magnesium levels - 2023-06-12

- Understanding evapotranspiration better - 2021-10-18

- Soil fungi connections - 2021-09-28